31/1/2023 – 2/2/2023

As we drove out of Saigon, the landscape rapidly became less urbanised, and farmland becomes the defining feature of the world outside of the bus windows.

The border crossing process was relatively straightforward – the bus dropped us off at Vietnamese exit control, and only a short amount of queuing was required. There was a British guy travelling on the same bus who had overstayed his visa-free period by several days, which caused a slight delay, but aside from that – no issues – and I was stamped out of Vietnam. At this point my bus, and the rest of the passengers, were stuck in no-man’s land between the two countries. The Cambodians, with Chinese investment, had built a large duty-free shopping complex in the area, and so we were taken there for a rest stop, before continuing through into Cambodia. At the border, my e-visa was taken off me, and I was stamped into the country – I took this opportunity to haggle and buy a Cambodian SIM card with some leftover Vietnamese Dong.

Cambodian Duty-Free building and the Bavet border

The bus stop was located in central Phnom Penh, on the banks of the Mekong. I was staying in a guesthouse a little to the south, a walk during which I quickly got acquainted with this small city. Cambodia is smaller and poorer than its powerhouse neighbour, which certainly shows in Phnom Penh, but it definitely has its own charm.

By the time I’d checked in, showered, and sorted myself out, the sun had set, and I headed out for food.

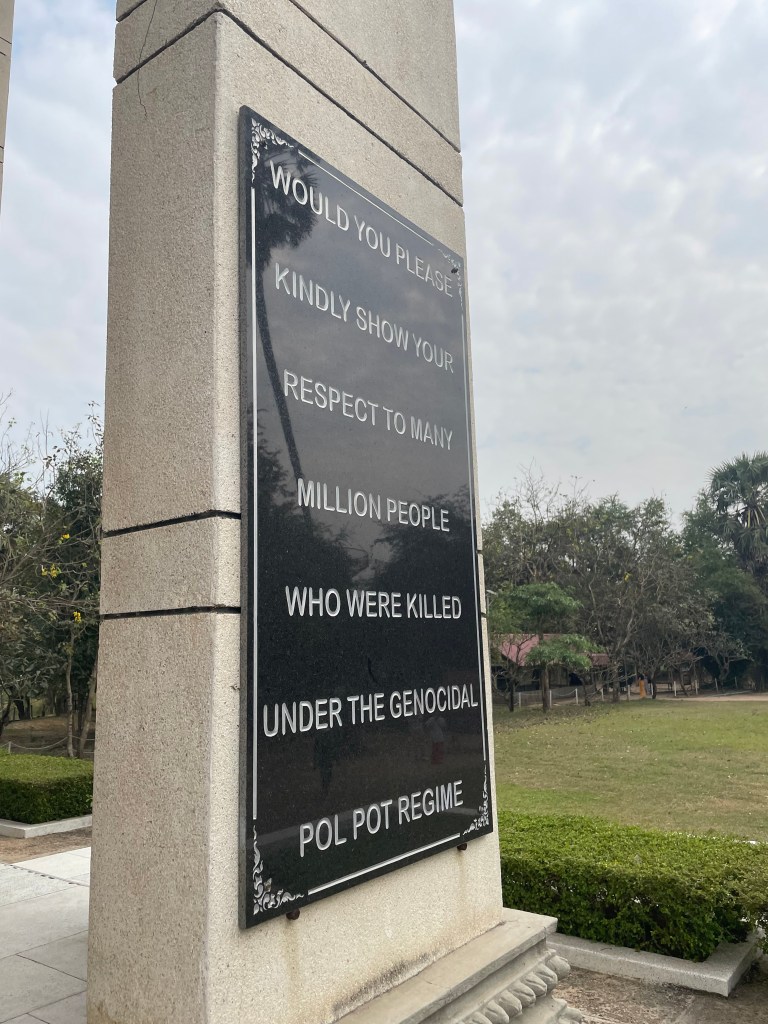

Cambodia has some pretty horrifying recent history, including the Khmer Rouge era during 1975 and 1979, when Pol Pot’s totalitarian regime wiped out almost 25% of the country’s population in one of the world’s most horrific genocides. Pol Pot aimed to transition the country into an agrarian socialist state, and engaged in policies including the forced relocation of city-folk to the countryside and mass murder of intellectuals, the abolition of money and property, as well as the removal of personal effects (everyone was to wear the same black clothing and have their hair cut the same). There was even a point where people who wore glasses were singled out for torture and execution due to the presumption that glasses = intellectual.

My day in Phnom Penh was not to be a happy one, but one in which I learned firsthand about the horrors of the Khmer Rouge regime. I visited Tuol Sleng Prison that morning, also known as S-21, a special prison that was used by the regime as a torture and execution site. Of the 20,000+ prisoners who walked through the doors of S-21 during its 4 years of operation only 12 are confirmed to have walked out alive. The prison is still in the condition it was found in, in 1979 when Phnom Penh was captured by invading Vietnamese forces, which means bloodstains, torture devices, and cells, are all still there. Throughout the halls of the building, some of which is now a museum exhibit, there are photographs of all of the inmates to pass through S-21, and most haunting of all, a map of Cambodia mounted on the wall, made entirely of human skulls.

I have just one photo from Tuol Sleng, of a photograph taken of Pol Pot during the Khmer Rouge’s time in power.

Pure evil.

Unfortunately, it gets worse. I spent my afternoon visiting the Choeung Ek Killing Fields, located to the south of the city. Choeung Ek was one of many such sites, where truckloads of prisoners were delivered, offloaded, and murdered by Khmer Rouge soldiers, who were often just young boys themselves. The Khmer Rouge wanted to conserve ammunition, and so people here were often killed with pickaxes and other implements. There is a tree in the middle of the field still covered in bloodstains from infants who were murdered against it. Human bones still little the fields, and whilst I walked around, I spied several, including a number of human teeth.

Tourists are given an audio guide, which contained the translated words of several people who were here during the Khmer Rouge rule, including a KR cadre who was part of the killing squads. In his words ‘either they died, or we died.’

At the centre of Choeung Ek lies a Buddhist stupa, built by the Cambodian government as a memorial. The stupa is filled with over 5,000 human skulls. Whilst visitors were encouraged to take a photograph of the stupa, so that the memory of the genocide wouldn’t be forgotten, I’ve chosen not to post that particular photo here – you can search it up online, if you wish.

I am someone who it fascinated by history, and that often fuels my travel desire (and this is why I chose to spend a few days in Phnom Penh) – but there are a variety of other things to do in Phnom Penh, should you ever visit, entirely unrelated to the genocide, and much more positive in nature.

However, if you do find yourself in the Cambodian capital – read up about the horrors of the regime, and visit Tuol Sleng and Choeung Ek – that way, this particularly horrifying event in recent history won’t be as easily forgotten.

Leave a comment